Excerpted from an article by Kerstine Appunn | –

( Clean Energy Wire ) – Germany’s energy transition is not only its main means for decarbonising the economy and creating an industrialised nation fed by renewable electricity to reach a 2045 climate neutrality target. The country’s famous Energiewende has also always been marked as an example to other countries of how such a transition is possible. But there is one aspect of it that is widely causing wonder and sometimes disbelieve: the nuclear phase-out. Why, at a time when emissions from fossil energy sources have to be reduced as fast as possible – and renewable energy sources such as wind and solar PV cannot (yet) support the country’s electricity needs – is Germany discontinuing the use of nuclear power, which is low in CO2. What are the reasons, repercussions, and benefits of this and how will it affect the country’s CO2 footprint, energy mix and supply security?

Facts of the German nuclear phase-out

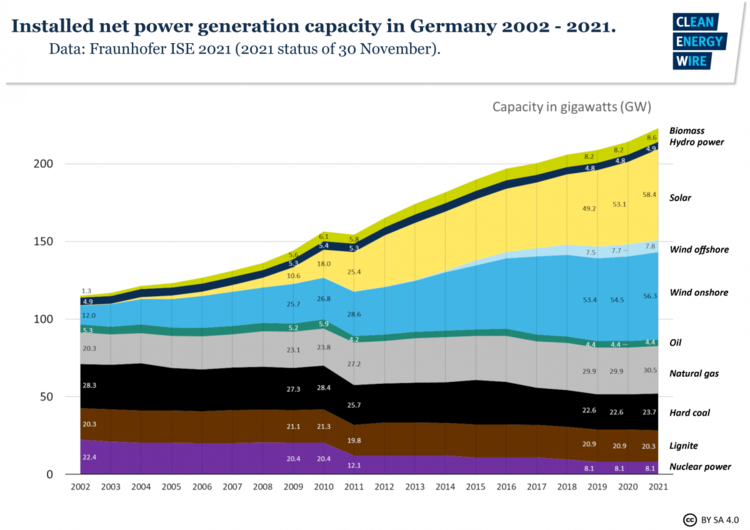

The last nuclear power plant in Germany will cease operation in December 2022. This definitive end-date is part of the 2011 Nuclear Energy Act (Atomgesetz) which withdrew the authorisation to operate nuclear reactors for power generation according to a phase-out schedule. From having a share of 22.2 percent in total electricity generation in 2010, the contribution of nuclear decreased to 11 percent in 2020. At the same time, renewables such as wind, solar PV and biogas provided around 45 percent of power generation in 2020. After three out of six remaining reactors are shuttered in December 2021 (Grohnde, Gundremmingen C and Brokdorf), only three (with a combined capacity of 4 GW) will remain in service throughout 2022 (Isar 2, Emsland and Neckarwestheim 2).

How did the nuclear phase-out come about in Germany?

The conviction that nuclear power should not be part of Germany’s energy mix has a long history and is deeply rooted in German society. After years of protests against nuclear power station projects in several locations, and fuelled by the accident at Three Mile Island (U.S.) in 1979 and the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986, the anti-nuclear movement resulted in no new commercial reactors being built in Germany after 1989.

When the Social Democrats and Green Party took over from a conservative government in 1998, they agreed a “nuclear consensus” with the big utilities operating the nuclear station fleet. By giving them certain power generation allocations, the last plant would be closed in 2022.

In 2010, a new conservative government under Angela Merkel amended this agreement, thereby extending the stations’ operating time by eight years for seven nuclear plants and 14 years for the remaining ten.

But after the accident in Fukushima, Japan, in March 2011, Merkel’s cabinet mothballed Germany’s oldest reactors for three months, before proposing to shut them down for good and phase-out the operation of the remaining nine plants by 2022.

Why the nuclear phase-out was the enabler of the energy transition

The reasons vary on why individual countries initially decided to commit to climate action, reduce the use of fossil fuels and, in 2015, sign the Paris Agreement which should lead all nations onto a path towards net-zero emissions. For some it was a question of securing a domestic power supply with the help of renewables. For some it only became a feasible idea after prices for wind and solar power installations dropped considerably, while others reacted to the brewing climate crisis and international pressure to act. The starting point of the energy transition in Germany, and with it the idea of climate protection, is the anti-nuclear movement and the rise of the Green Party at the end of the 1970s. As opposition to nuclear power and support for the Greens grew – resulting in their election into government in 1998 (see above) – so did the general public’s awareness of environmental and climate protection.

“It is true that, at the beginning of the energy transition in Germany, we argued mainly about nuclear power. But in parallel to the nuclear phase-out, we created the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) in 2000. With this law, we wanted to prevent the nuclear phase-out from leading to an increase in fossil power generation and a burden on the climate. In reality, much more has been achieved in the last two decades. Renewables generate much more electricity in Germany today than nuclear power plants did in 2000,” Rainer Baake, managing director of the Climate Neutrality Foundation and one of the architects of Germany’s first nuclear exit legislation and former energy ministry state secretary, told Clean Energy Wire.

The first EEG, which gave a feed-in payment to producers of wind and solar power, initiated a renewables boom, lowered the price for the new technology considerably, and saw the share of renewables in the German power consumption grow from 6 percent in 2000 to 46 percent in 2020. This transition in the power supply – known as “Energiewende” – raised the awareness and ambition to also decarbonise other sectors and led to the 2020 decision to phase-out coal power by 2038 at the latest. The new German government wants to move this end-date forward to 2030 . . .

How does Germany want to make net-zero happen without nuclear?

Germany’s energy transition in the electricity sector has turned into a comprehensive plan to decarbonise the entire economy and reach net-zero greenhouse gases in 2045. With nuclear power and coal out of the picture by the end of the decade, the new government – which is adhering to the previous government’s climate targets – is putting the focus on renewables growth. Its aim is to reach a share of 80 percent renewables in electricity demand (which is envisaged to grow). Several “Germany net-zero” studies have shown that a system based on renewables is possible.

The government acknowledges that a fleet of flexible (and hydrogen-ready) natural gas plants will be necessary to run a stable power system. Between 2019 and 2030, 21 GW of lignite and 25 GW of hard coal capacity will be shuttered, research institute EWI has calculated. Existing over-capacities, new flexibility options, and efficiency – as well as the addition of renewables capacity – will mean that not all of this controllable power plant capacity will need to be substituted, German energy industry association BDEW says. “But an earlier coal phase-out means we will need an additional 17 GW in gas-fired capacity,” BDEW head Kerstin Andreae said.

Germany will have to be even more interconnected with neighbouring countries to exchange (renewable) power in times of low wind and little sun. It will need to upgrade its grid system. To supply power stations and industry, large amounts of hydrogen will be needed and imported.

Why doesn’t Germany get an energy system with both renewables AND nuclear?

Its advocates portray nuclear power as a stable energy source that can help to secure supply during times of little wind and sun. “We need renewables to be complemented by a reliable, 24/7 energy source,” said James Hansen, a climate scientist at Columbia University when taking part in a pro-nuclear climate demonstration in Berlin.

But German energy experts have their doubts about whether fluctuating renewables are best complemented by nuclear. “A climate-friendly electricity system dominated by weather-dependent production from wind and solar plants requires a great deal of flexibility to balance fluctuating supply with fluctuating demand. Nuclear power plants are technically and operationally designed for production that is as constant as possible. They are the exact opposite of what wind and solar need as partners,” Rainer Baake said . . .

What’s more expensive – renewables or nuclear?

One of the reasons why it is an obvious choice for Germany to make wind and solar its main power source rather than nuclear, is that new renewable installations have become cheaper than all other electricity sources – especially where a CO2 price is applied.

According to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2021 and Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Institut), the energy costs for nuclear power generation are currently 15.5 cents per kilowatt hour, compared to 4.9 cents for solar energy and 4.1 cents for wind power.

The British government has given a price guarantee of 11 cents per kilowatt-hour for 35 years to the nuclear power plant project Hinkley Point C. In Germany, feed-in tariffs for onshore wind and solar PV are between 6-7 ct/kwh or, in some tenders, even lower. Offshore wind parks are now being built without any government support.

New reactor projects often turn out to be much more expensive than envisaged. The costs for a new “Evolutionary Power Reactor (EPR)“ in Flamanville, France, have risen from 3.4 billion to more than 19 billion euros, while the project will likely take at least 11 years longer than planned. Similar price hikes and delays have occurred in the UK, Finland and the U.S.. . .

What is different in Germany compared to other countries in Europe which embrace nuclear as a CO2-free solution?

Germany not only has strong public support for, and a long history of, anti-nuclear sentiment, it also has only 11 percent of nuclear left in its power mix. Leaving it behind entirely is therefore a more obvious and easy decision than for other countries, such as France, where the share of nuclear power in domestic generation stands at 70.6 percent, but also in Bulgaria with 40.8 percent, in Sweden with 29.8 percent (in Spain: 22.2%, Russia at 20.%, United States at 19.7%, UK 16%, all in 2020).

Historians also explain the different attitude towards nuclear with the different reactions to the Chernobyl accident, which was felt much closer and more threatening to Germans compared to French or UK citizens. Another explanation for Germany’s sensitivity to nuclear power is that early on, the post-war critique of nuclear weapons was linked to the civilian use of nuclear fission. (A second wave of the German peace movement in the 1980s would also bolster a younger generation’s resistance to nuclear power.)

And even if there are people who make a case for nuclear for climate protection reasons, the exit has now proceeded too far to be reversed, and there is simply no influential political power that would consider re-opening the painful, decade-long debate on nuclear power that has finally been put to rest.

Kerstine Appunn is a staff Correspondent for Clean Energy Wire. She joined after working at the Schleswig-Holsteinischer Zeitungsverlag newspaper groups, where she covered general politics as well as energy and climate policy. She has an MSc in Global Environmental Change from King’s College London and a law degree from the University of Kiel. She has also worked as a consultant for the International Institute for Environment and Development in London.

Excerpted from Clean Energy Wire

“Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY 4.0)” .

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved